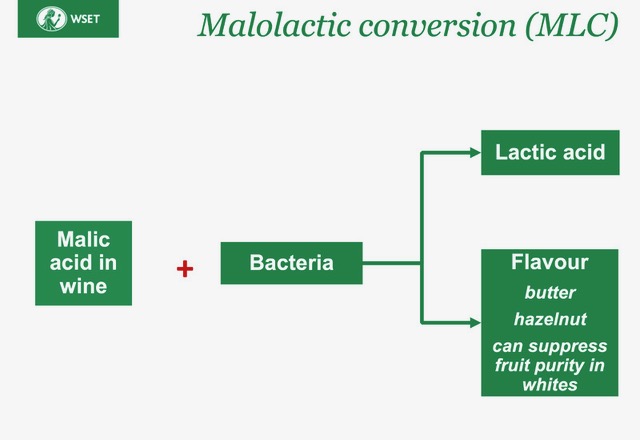

Malolactic Conversion

We begin with malolactic conversion. This winemaking technique can sometimes be recognized in white wines by aromas such as butter and cream. But let’s first take a closer look at the name itself, as it contains valuable information to help us understand this process.

Malo-lactic Conversion:

- Malo refers to the Latin word malus, meaning apple.

- Lactic refers to lactic acids, which are found in various dairy products.

- Conversion indicates a transformation or change.

Malic acids to lactic acids

So, malolactic conversion involves the transformation of malic acids into lactic acids. In the past, this process was also called malolactic fermentation, but since it is not carried out by yeast cells, most people now prefer the term “conversion.” Bacteria, such as Oenococcus oeni, consume the malic acids in the wine and then release lactic acids and CO2.

It’s important to note that malic acid makes up only a small percentage of the total acids in wine, and this percentage varies depending on the grape variety. The majority of acids in wine are tartaric acids. Therefore, malolactic conversion doesn’t transform all the acids in the wine, but rather just a small portion.

As you may have noticed when tasting wines, the aromas associated with lactic acids aren’t present in all white wines. A winemaker decides whether to allow malolactic conversion to occur or not. Naturally, this process would always take place unless the winemaker intervenes to prevent it. Below, I’ll explain the options for doing so.

When yes and when no?

The main trigger for lactic acid bacteria to become active and perform the conversion is temperature, ideally between 18 and 24 degrees Celsius. This immediately highlights a key difference between red and white wines. While red wines almost always ferment at temperatures above 18°C, white wines—especially fresher, aromatic, and often simpler ones—are frequently fermented at controlled temperatures significantly lower, between 12°C and 15°C. In such wines, the low temperature prevents malolactic conversion. After fermentation, these wines are typically treated with sulfur dioxide (SO2), which kills the bacteria responsible for malolactic conversion and prevents it from occurring even if the temperature later rises above 18°C.

Because the aromas resulting from malolactic conversion, such as butter and cream, are mainly recognizable in white wines, we’ll focus further on white wine production.

With aromatic white

A producer of a fresh, aromatic white wine, such as Sauvignon Blanc from Marlborough, will choose not to allow malolactic conversion. In this wine style, buttery and creamy aromas are undesirable because they detract from the wine’s expressive character. Additionally, lactic acids taste softer and rounder than malic acids. A producer aiming for maximum freshness will block malolactic conversion to preserve the malic acids.

For non-aromatic white

Conversely, Chardonnay producers more often allow this conversion to take place. Chardonnay grapes are inherently less aromatic than Sauvignon Blanc and leave more room for flavors resulting from winemaking choices. When asked what flavors they associate with Chardonnay, most people will mention “butter” and “vanilla.” While these answers are correct, these flavors don’t come from the grape itself but result from techniques applied by the winemaker during vinification. Here, consumer expectations drive the production choices: if people expect buttery and vanilla notes in Chardonnay, producers ensure their wines meet this expectation.

That said, not all Chardonnays display these aromas—such as those from Chablis in northern Burgundy. Many people have heard of this famous wine region but are less aware that Chardonnay is the sole grape variety used there.

Tasting tips

Would you like to improve your ability to identify malic and lactic acids in wine? Below are some wine suggestions to help you build strong references. Tip: Alongside assessing acidity levels (low, medium, high), try to discern whether the acids feel rounder or sharper in your mouth. This can help you distinguish between wines with malolactic conversion and those where the process was blocked.

Wines WITH malolactic conversion:

- Chardonnay from California (e.g., Bernardus, Coppola Director’s Cut)

Wines WITHOUT malolactic conversion:

- Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc

- Picpoul de Pinet

It’s also highly interesting to compare two white Burgundies:

- Chablis (no lactic acids)

- Côte de Beaune (contains lactic acids)

Make sure to get good advice when purchasing these wines! There are Chablis wines WITH malolactic conversion and Côte de Beaune wines WITHOUT it.